17 Aug We all play language games – but the boundaries are getting dangerously blurred

When we talk, we follow certain ground rules, which are set out in what philosophers call “language games”. Each game has its own set of rules – but problems arise when not everyone is clear which game is being played.

Perhaps most important is the informing game, in which we use words to give people useful information about the world: “It’s raining outside”, “The meeting is in Room 12”, “That’s vodka, not water”.

In this game, the No. 1 rule is to tell the truth. If we break it, we can rightly be held to account for lying, or at least misleading. Without this truth-telling rule, our interactions in many walks of life would break down, from the science lab to the schoolroom to the courthouse, and anywhere else that evidence, facts and a shared understanding of reality matter.

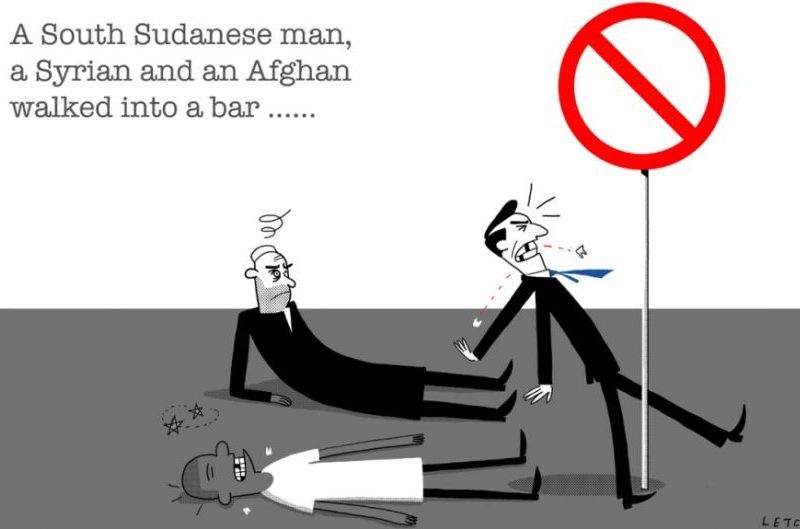

But there are also language games in which the truth-telling rule does not apply. If I say that a horse walked into a bar, you should know I am not playing the informing game. To complain that I am lying, or to demand evidence— which horse? which bar? — would be like a soccer player on the rugby field asking why other players are handling the ball.

Mixing the rules of our language games is a major factor in the deepening crisis of “post truth” public discourse. Consider Donald Trump, who has made more than 2000 false statements in public since his inauguration as US President, and countless more before that.

To cite just one example, in a 2016 campaign speech Trump stated that US black youth unemployment was at 58 per cent, when in fact the US Bureau of Labor Statistics put the figure at 21 per cent. Fact-checkers wanted to hold Trump accountable for having broken the truth-telling rule. But as author Salena Zito explained, his supporters couldn’t have cared less about the facts: “When Trump makes claims like this, the press takes him literally, but not seriously; his supporters take him seriously, but not literally.”

For supporters, Trump was not playing the informing game, he was playing the signalling game. It’s like joking, but without the laughs. In the signalling game, language is for aligning with people, affiliating with them, tapping into their views and feelings. Not for conveying the facts.

Or consider Senator Fraser Anning’s maiden speech to Parliament this week. In a formal, high-stakes, on-record speech, one might think that firm evidence would be indispensable to a solid argument, yet fact-checkers found numerous inaccuracies. Then again, as a statement intended to set the tone of Anning’s tenure and to grab hold of a news cycle, perhaps facts were less important for Anning than signalling the intended sentiment.

With “dogwhistle” expressions, a speaker can signal certain ideas without being accountable for having expressed them. We might ask whether Anning’s reference to the “final solution” was a botched attempt at dogwhistling, or whether it was meant to be the foghorn that it was.

The problem is not confined to the political right. Take the recent controversy over The New York Times hiring author Sarah Jeong. She has come under fire for the content of her Twitter feed over recent years, including quips like “f— white women lol” and “#cancelwhitepeople”.

As author Iona Italia put it, Jeong’s supporters argue that “this kind of speech cannot be considered racism, because its intent is simply to signal allegiance to the cause of social justice”. Jeong herself said that the tweets were “intended as satire”. Either way, when being taken at their word, this speaker’s response is not to defend the words, but to say that they were part of a language game in which the truth-telling rule did not apply.

The problem is that the “don’t take me literally” defence can always be made after the fact, when the content of what one said has turned out to be problematic. How do we know what games people really were playing and when the signalling defence is an attempt to escape accountability?

Edgy humour has always exploited this ambiguity: maybe I mean this, maybe I don’t. Is the onus on us as listeners and readers to determine which language game a speaker was playing before we call them out for breaking the rules? In private life, perhaps, but in public discourse, we are not, and should not, be free to just play any old game with language. Why not? Because truth matters. If I take a falsehood literally, I am now ill-informed and in the real world this means I may then make poor decisions with real consequences.

Consider the reckless statements about smoking that British politician Nigel Farage has made in public: that people should ignore the World Health Organisation’s recommendations, because the organisation is “just another club of ‘clever people’ who want to bully us and tell us what to do”; that “the doctors have got it wrong on smoking”. These statements may have been good plays in the signalling game, but public statements will always circulate beyond their original context and so the collateral effects of such signalling are plain dangerous.

The philosopher Harry Frankfurt uses the technical term “bullshit” for the language game in which truth does not enter into the rules. It is the most dangerous game in public discourse because it threatens to normalise the idea that people are not accountable for saying things that are false. Of course, the “don’t take me literally” game has its place, but in public discourse it introduces ambiguities and escape hatches that play on the wider audience’s lack of common ground: if only you were part of the in-crowd, you’d have known not to take me literally.

If we continue to allow signalling and other forms of “bullshit” to corrode the link between language and truth, we stand to lose the most precious thing that language gives us: the capacity to anchor social life in a common frame of knowledge and understanding of reality.

Reality does not care about our social signals. Being sceptical of “clever people” won’t stop smoking from damaging your health. Only by privileging the game of evidence-based reasoning can we find paths that distinguish the true from the false, the safe from the dangerous, the sensible from the stupid, and even the good from the bad.

Nick Enfield is a professor of linguistics at the University of Sydney and head of the Post Truth Initiative. He is a panellist in a discussion on truth decay at the University of Sydney’s US Studies Centre on August 22.

Originally published on The Sydney Morning Herald

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.