17 Nov We’re in a post-truth world with eroding trust and accountability. It can’t end well

In our new normal, experts are dismissed and alternative facts flagrantly offered. This suspicion of specialists is part of a bigger problem

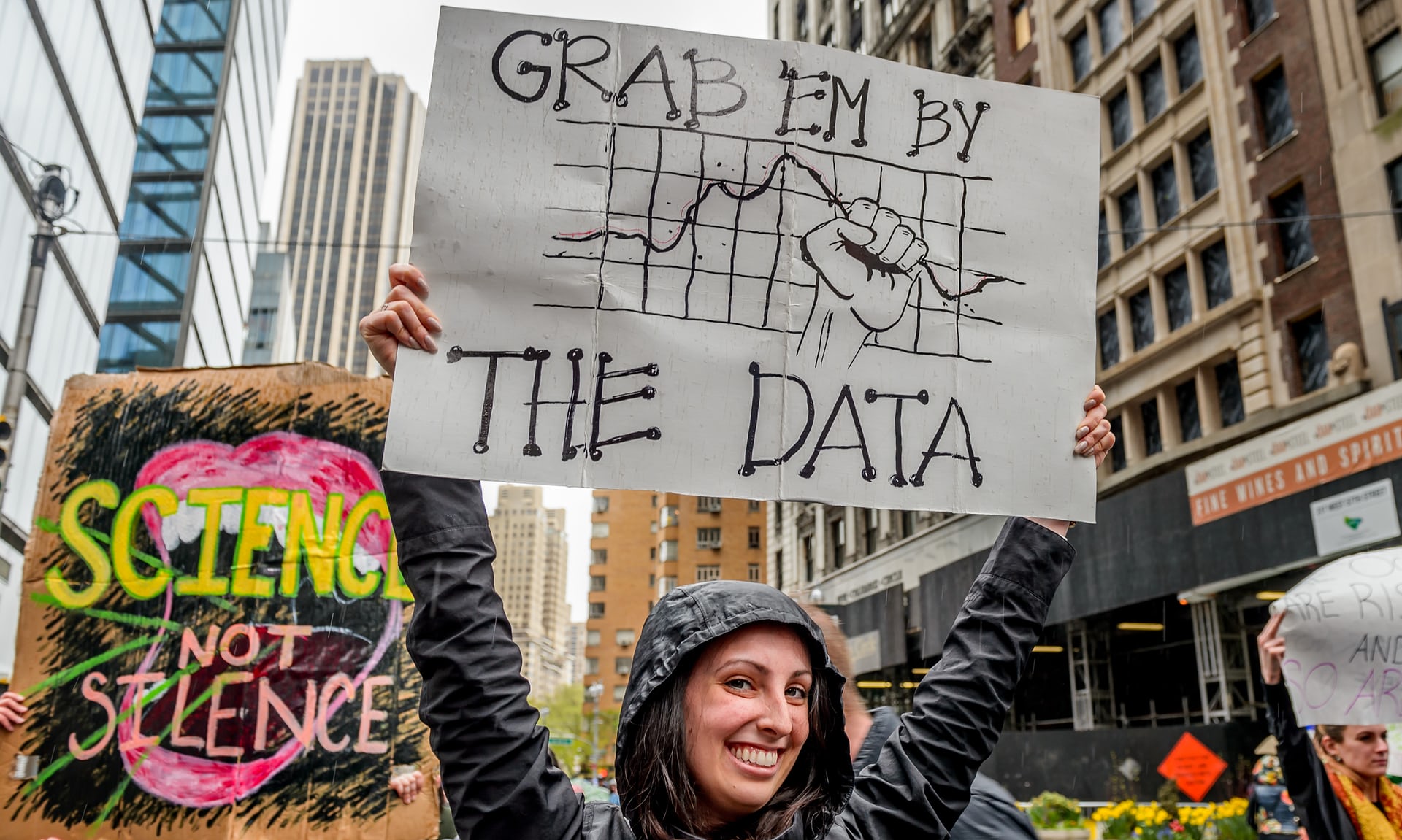

Image: March For Science In New York City, 22 April 2017. Photograph: Erik McGregor/Pacific/Barcroft

We often defer to others’ expertise, and for good reason. The entire edifice of modern society only exists thanks to the division of labour, from construction to machine operation to medical treatment. The system works as long as we have trustin others’ knowledge, skills and intentions.

This trust is often tested, most notably of late in relation to those who specialise in politics. People-powered movements from anarchism to populism want to see equality of participation in political decision-making. Indeed, this is at the heart of all versions of democracy. It raises the question of whether we should trust political insiders.

Populism has done well by questioning the value of career politicians and other members of the establishment, instead celebrating the possibility that positions of political power can, and should, be occupied by outsiders. Pauline Hanson surprised many by winning office in Queensland in the 1990s on a “people versus elites” campaign. Many similar examples have since gone all the way to the top. Many argued that Donald Trump was not qualified for the US presidency because he had never held public office and did not have the skills for the job. Those arguments failed to prevent him gaining office.

Those who prevailed have exploited the tension between ideals of equal access on the one hand, and deference to expertise on the other. While we might debate the wisdom of trusting political insiders, the suspicion of specialists and experts has begun to contaminate a much bigger ecology of knowledge and practice in our society.

The result is post-truth discourse. In our new normal, experts are dismissed, alternative facts are (sometimes flagrantly) offered, and public figures can offer opinions on pretty much anything. And thanks to social media, pretty much anyone can be a public figure. In much public discourse, identity outranks arguments, and we are seeing either a lack of interest in evidence, or worse, an erosion of trust in the fundamental norms around people’s accountability for the things we say.

Australia offers its share of examples. Last year, in relation to the Adani coal mine, Anthony Lynham stated that “Queensland taxpayers will not be funding any infrastructure for this project”, but Queenslanders as federal taxpayers would fund infrastructure via the proposed billion dollar loan to Adani. And when Tony Abbott opened the massive Caval Ridge mine in Central Queensland in 2014, he said “coal is good for humanity”.

The overwhelming majority of people who are professionally qualified to evaluate scientific evidence on the matter know otherwise .

This cannot end well. We can’t afford to dismiss the testimony of those with scientific and technical expertise. Like the airline pilots who we rightly trust to fly our planes, scientists have knowledge and skills that many of us both lack and need.

The scientific community is responding with a growing counter-movement. A global March for Science on Earth Day in April 2017 saw more than 600 cities participate. Thousands have signed a pro-truth pledge , with commitments including “fact-check information to confirm it is true before accepting and sharing it’, “reevaluate if my information is challenged, retract it if I cannot verify it”, and “distinguish between my opinion and the facts”.

Sticking to commitments like these is hard work and does not necessarily come naturally. The struggle to do so encapsulates two fundamental things about what it means to think and talk like a human.

The first is that while human higher reasoning is a celebrated capacity of our species, we are in fact notoriously poor reasoners. Nobel Prize winner Daniel Kahneman, among many others, has shown that our reasoning is riddled with cognitive bugs and biases. The confirmation bias is one of the most insidious. We are highly likely to believe or at least accept and repeat statements that support our established views, even when little or no evidence is given to support those statements. Yet we are unlikely to accept or repeat statements that go counter to our established views, even when they are well-supported by evidence. This bias is the engine that drives the click-by-click spread of fake news and other dangerous nonsense.

The second thing is that humans are psychologically capable of the remarkable feat of focusing our attention on our own thought processes and deliberately overriding them. We can identify our own flawed habits of thinking and then use more deliberate cognition to outsmart these habits and avoid the pitfalls. Much of higher learning involves the cultivation of just this capacity.

Because the deliberate attention to our own faults of reasoning requires vigilance, people need to be motivated to put in the hard work needed. The solution that has worked well so far is to maintain social norms by which we agree to be accountable to evidence and other elements of rational argumentation. This in turn has given us reason to rein in our more instinctive, biased patterns of reasoning.

The post-truth crisis is none other than the breakdown of these norms.

Originally published on The Guardian Opinion

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.